Covid-19 and Sport

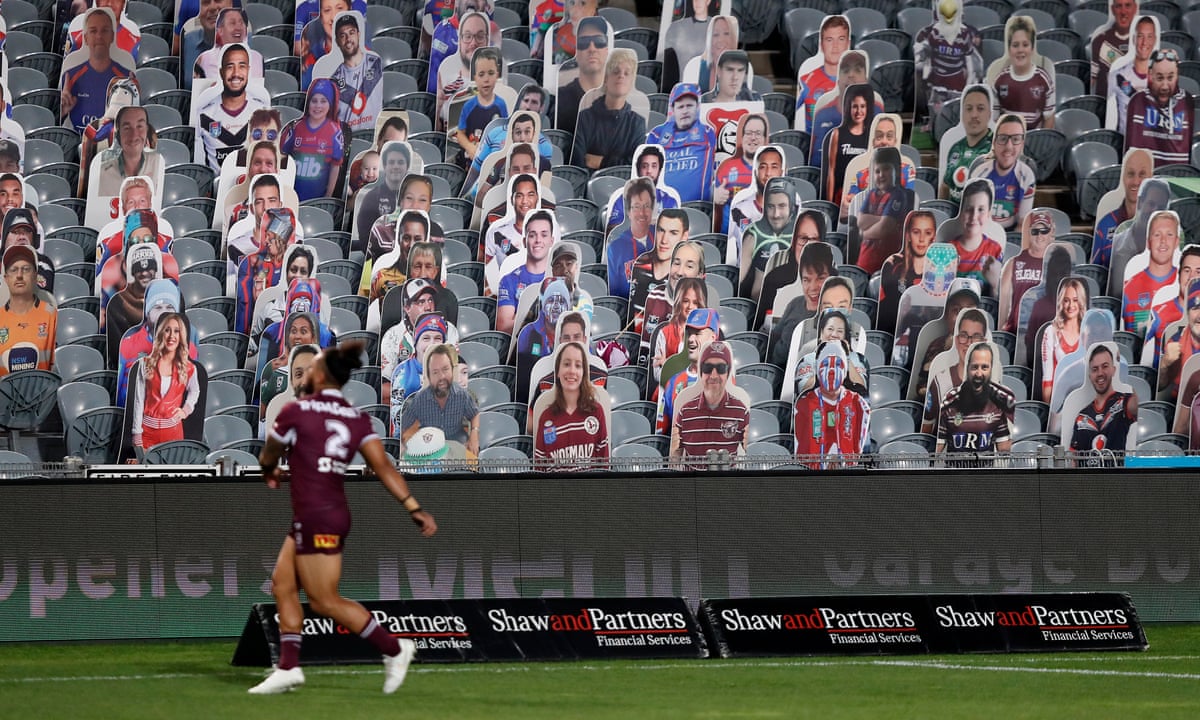

The Pandemic and subsequent lockdown restrictions brought sport and much physical activity to a grinding halt in March 2020. Although government guidelines decreed physical activity a legitimate reason for leaving the house under lockdown, the closure of gyms, leisure facilities and the ban on group activities and team sports drastically reduced the nation’s options for exercise. Sport is also, of course, big business, contributing £39 billion annually to the British economy, and an estimated $471 billion worldwide. Elite sport was soon back underway as sports such as football and Formula One ensured that their lucrative commercial contracts were fulfilled. But events were staged behind closed doors and cheering crowds were replaced by cardboard cutouts and pre-recorded soundtracks. In the lockdown hiatus some individual sports in the UK were allowed to recommence; sailing, tennis, golf and grouse-shooting among them. Much grassroots sport however, has faced severe financial difficulties, from lower-league football clubs struggling with loss of income to yoga teachers having to transfer their business online. How has the pandemic affected our physical health? Has home working opened up opportunities for increased exercise or have people become more sedentary? To what extent have class and gender affected patterns of exercise and physical health? How have children been affected? What have been the effects of the loss of the collective experience of mass spectator sports? How have these changes impacted on our mental health? Will the pandemic permanently damage grassroots sport or will the changes be merely temporary? Will some sports gain from the crisis and others suffer, and if so, which ones? Has the pandemic accelerated a shift to esports and what will be the consequences? Has the business model for commercial sport been permanently altered? Will sport sustain its central position in cultural life post-pandemic?

On 15th April 2021, the Pandemic Perspectives group debated these issues, guided by Grix, Brannagan, Grimes & Neville’s excellent paper, ‘The Impact of Covid-19 on Sport‘, from the International Journal of Sports Politics and Policy; Kieran Fallon’s short piece on, ‘Exercise in the time of Covid-19‘; A wide range of data from Statista.com’s ‘Coronavirus (Covid-19) disease pandemic effect on the Sports Industry’ and a Guardian editorial of 12 April 2021, ‘The Tokyo Olympics: Should the show go on?‘ The impact on Women’s participation in sport was explored using two articles, an optimistic piece by Women In Sport from June 2020, ‘Lockdown Research: Implications for Women’s Participation‘ and a later, more circumspect piece from The Conversation, ‘A year into the pandemic, COVID-19 Exercise slump has hit women harder‘.

Christopher Griffin opened the debate by commenting on the decision to stage the 2021 Tokyo Olympics. He noted that despite the high prevalence of Covid-19 in Japan, the ban on international spectators and the severe restrictions on Japanese attendees, the games was still going ahead, albeit in front of largely empty stadiums. He argued that as this would remove much of the celebratory and carnivalistic elements of the event, the decision to stage it in the midst of the pandemic could only be attributable to the scale of commercial interests already vested in the games. He reminded the group of some of the more egregious characteristics of the Rio Olympics, with human rights abuses and walls built to hide the city’s slums from the gaze of international visitors. Acknowledging that the Olympic games were fundamentally business marketing events, he also noted their extraordinary popularity with an audience of 3.6 billion people for the Rio games. He also broadly concurred with Durkheim’s conception (quoted in Grix et al) that mass attendance of spectators created a ‘collective effervescence’ which perhaps did constitute a necessary ‘societal corrective’ for people in difficult times. He noted the capacity of sport to create collective goodwill, citing, as a long-distance runner, the spontaneous support and encouragement of crowds lining the route. David Christie referred to the work of sports historian David Goldblatt, ‘The Games: A Global History of the Olympics‘, which digs deeply into the commerce, corruption and politics of the Olympic movement from its inception. He argued that although any such ‘societal correction’ provided by the Olympics could be viewed in terms of ‘bread and circus’ to keep the masses docile, there was something in the collective experience that was both necessary and desirable. He noted that Grix et al’s article linked the crowd experience to chemical changes in the brain, eliciting the secretion of Serotonin and consequent sensations of joy and euphoria. Richard Kendall was more doubtful. Noting that Rio too, had taken place during a pandemic (the forgotten zika virus) he noted that commercial imperatives inevitably overrode any other considerations, citing the appalling human rights record of the next football World Cup hosts, Qatar. He noted that while no one expected to find any morality in professional football, conceptions of amateurism, and the ideal of joyful participation for its own sake still lingered around the Olympics. It was collectively felt that the decision to stage the 2021 games was probably unwise.

Ronan Love moved the discussion on to football, noting the contrast between the rapid resumption of the elite competitions and the damage done to lower-league clubs, who, without lucrative TV deals or spectators had been pushed to the brink financially. He noted the complete victory of commercial interests with matches played in empty stadiums with fake crowd noises, perhaps destroying once and for all the myth of football clubs organic relationship with their supporters. He acknowledge that although some monies had been redistributed from the premier league clubs to the lower divisions, the ‘big six’ British teams and the European footballing giants had also used the pandemic to try and ensure an even greater proportion of revenues by reforming the Champions League. Kendall was unsurprised by this, considering the ultimate ‘distancing’ of supporters from clubs brought about by Covid-19 as merely an acknowledgement of what had already happened with football, where support of a club had long since become little more than a form of ‘brand loyalty’ akin to that held by people toward prestige-awarding consumer goods. Christie disagreed, citing the extraordinary longevity of football clubs founded in the Victorian era as evidence of something beyond mere commercial exploitation, and that for smaller towns and clubs, a sense of place and community was still a vitalising force. He confessed his lifetime allegiance to the historically small and unsuccessful Brentford FC, and offered the digital-works oral history of the club, ‘Push-up Brentford’, that he had participated in, as evidence in support of his views. It was noted that this form of identification was typically working-class and masculine and had never therefore held the allegiance of much of the community. Christie argued that the gender balance in male football crowds had altered significantly in the last decade, and the rise of women’s football was now a significant force. The post-pandemic future of football clubs and grassroots sport was discussed. Christie pointed out that in football, only Dover Athletic in the National League had ceased to function so far, but given the almost complete loss of revenue for lower-league clubs during the pandemic, debts would be rising and more would be sure to follow. Griffin argued that for grassroots and community sports clubs, their future rested on the post-pandemic fiscal response, challenging the assumption in the Grix paper that a return to austerity was inevitable, he reiterated James Meadway’s view that austerity was a political choice not a necessity. He noted that the ‘callous genius’ of successive conservative governments had been to drastically reduce funding to local authorities (by 38%, 2010-18), thus forcing them to cease funding non-statutory services such as youth clubs and community groups, while passing the blame onto local government. Love noted that local football clubs fell outside of political logistics, being not deigned worthy of political sport and not sufficiently lucrative to be attractive to private finance.

Griffin raised the issue of the gendered impact on sport of the pandemic. He noted that it had been widely observed that the impact of the pandemic had been greater on women, in terms of disproportionate job losses in the caring professions and hospitality, and in terms of their role of primary care givers and the gendered distribution of household chores falling on women. Although the Women In Sport report had suggested that for some women the pandemic had opened up opportunities to exercise, the long-term effect as revealed in The Conversation article suggests that women’s participation in sport had declined considerably over the last year. Hanan Fara noted that recent research by Nottingham Trent university on elite women athletes had shown 80% to have been negatively effected by the pandemic. She argued that the pandemic had imposed further burdens on women, particularly those with young children and single parents, restricting opportunities to exercise and accelerating the pre-existing gap between male and female participation in sport. She did, however, note an increase in women’s running groups, and saw the pandemic as facilitating more familiarity with online exercise sessions and apps such as ‘Our Parks’ that encouraged local group exercising.

The group speculated over whether the nature of sport had changed as a consequence of the pandemic. Love noted that snooker’s impresario, Barry Hearn, had seen the pandemic as an opportunity to increase the profile of a ‘sport’ that, with only two players taking turns at the table was naturally socially distanced. He noted that snooker clubs had been closed under lockdown, and wondered if the televised professional game had indeed earned new converts. Christie raised the question of the pandemic’s impact on the growth of esports. Acknowledging that it had been gaining momentum before the pandemic hit, he noted that, for example, the credibility of online racing games had been enhanced by the participation of Formula One driver Lando Norris. Fara noted that watching others play esports had become much more common under lockdown as there was little else to do, and Sadegh Attari reminded the group of the new popularity of marble racing, with its own YouTube channel Jelle’s Marble Runs. New avenues for the commercialisation of sport and exercise were noted. Alastair Gardner’s sense of being inundated by ads for a Peleton are born out by an enormous increase in sales of home-exercise equipment during the pandemic, and he noted that virtual cycling and running races were now common among enthusiasts and had also developed into a new spectator sport. Gardner also noted that sports gambling, already endemic in sport, had accelerated even faster under the pandemic. He explained that in the US, many states had moved to legalise in-game betting and that the NBA had fully integrated in-game gambling into its business model. E sports betting has also risen rapidly. The even greater periods of time spent online during lockdown brought up the question of the increased power of algorithms in shaping peoples relationship to activity and self-image. Gah-kai Leung expressed his concern at the rise in advertisements for life-coaching, arguing that the ‘happiness industry’ was profiteering off people’s aims of self-actualisation. There was some discussion about the impact of lockdown on the self-image of those (most of us!) who had over-eaten and under-exercised during the pandemic. Fara noted that fit-bit sales had boomed under lockdown and anticipated a huge marketing push on selling methods of reducing weight post-pandemic. She suggested that these would inevitably be targeted at women. Gardner noted that the parallel development of the Black Lives Matter movement during the pandemic had also brought about, at least surface, changes in sport. Noting that in the NBA, where 80% of players are African-American, a greater awareness of the exploitation of black bodies and black culture and the racist politics of sport had risen up. He noted that the hostility of the right-wing press in the US and the (white) owners of basketball teams to black athletes campaigning ‘outside their lane’ had lessened, and that BLM flags were now flown at NBA games. Leung considered this to be the most cynical form of ‘virtual signalling’ by unreformed team-owners.

There was much more, join Pandemic Perspectives to have your say or set up your own group…