Covid and Time

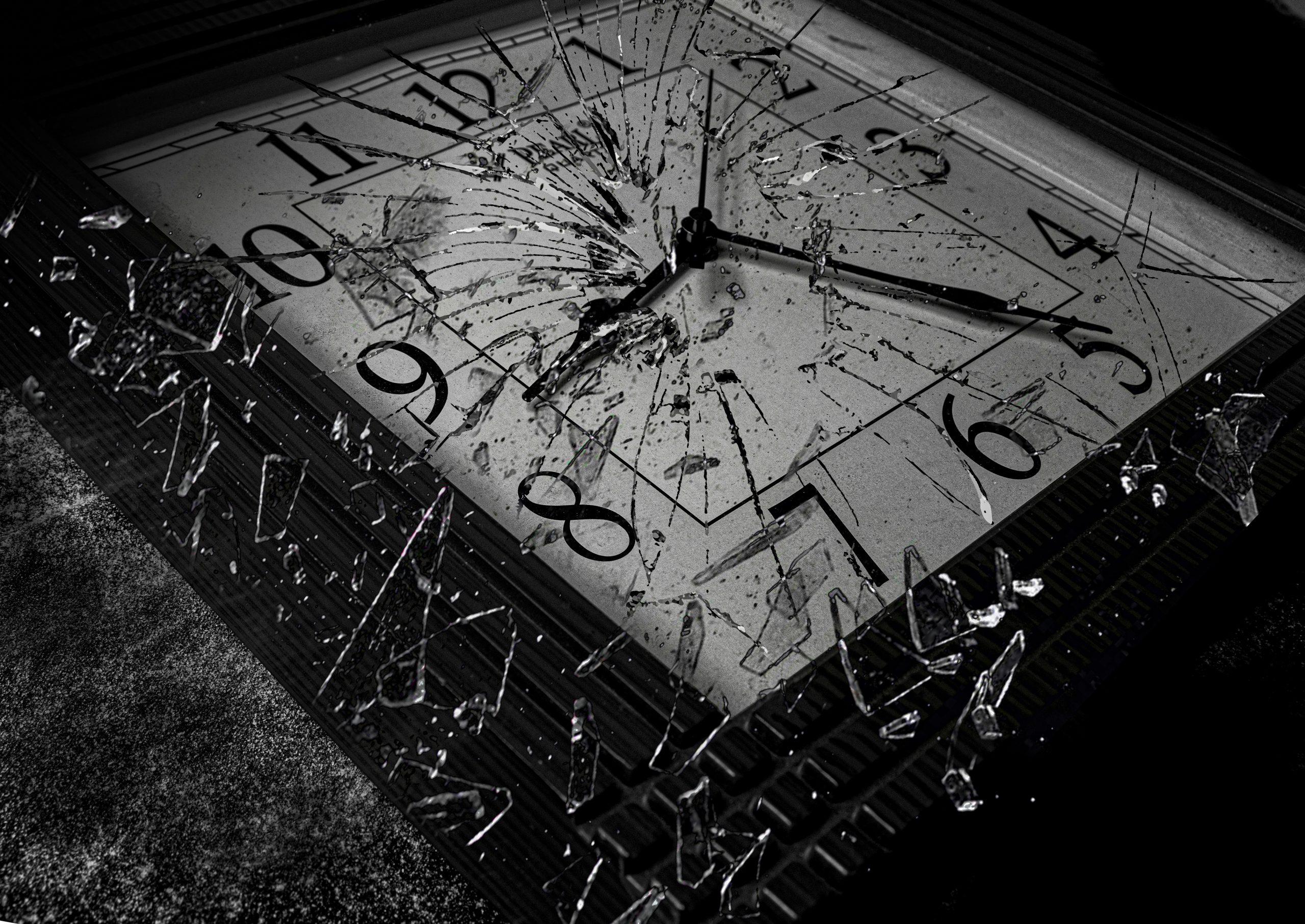

To what degree has the Pandemic altered our perception of time? For many the sense of time progressing has ceased, replaced by an ‘endless’, looping, repetitive sense of time. How widespread is this feeling and what are its consequences? What drives our sense of the perception of time and how has this changed? How does this effect our mental health and sense of well being? How has it affected our dreams and the division between dream and waking states? Has our temporality been permanently affected? Has the mechanised ‘clock-time’, begot by the industrial revolution been permanently transformed, or will it reset when lockdown is over?

On 25 February the Pandemic Perspectives group debated these issues. To give a broad perspective the group were guided by David Christian’s paper ‘History and Time‘, from the Australian Journal of Politics and history, and Reinhard Koselleck’s work ‘Futures past: The semantics of historical time’. On the impact of the Pandemic; Sara Linberg’s ‘Perception of Time has shifted during Covid-19; Holman and Grisham’s work ‘When time falls apart: The Public Health Implications Distorted time Perception in the Age of Covid-19; Nicole Westman’s ‘The Pandemic Ruined Time’ and Tore Nielson’s Scientific American article, ‘The Covid-19 Pandemic is changing our dreams’. Reference was also made to Francois Hartog’s, ‘Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and Experiences of Time; Johnny Harris’ YouTube video on international time zones; ‘Why Britain is the Centre of the World‘; an Independent article, ‘Norwegian Island Wants to Erase the Concept of Time‘ and Dawson and Sleek’s ‘The Fluidity of Time: Scientists uncover how emotions alter time perception.’

David Christie began by attempting to summarise Christian’s article. In it Christian notes that time is normally considered to flow, and to flow in way that seems linear, directional, regular and even. He points out that this this Newtonian ‘clock-time’ does not conform to scientific understandings of time, where it can move backwards and is relative to the speed an object is travelling at, or to our psychological experience of time, where it appears to move at different rates dependent on our activities (boredom, excitement), and is not the way that pre-agricultural societies experienced time, where it was viewed as endlessly cyclical rather than progressive. Christian argues that our modern notions of progressive time separated from cyclical ‘nature time’ (rhythm of days and seasons) with the onset of agriculture and intensified during the industrial revolution, becoming a fully anthropogenic ‘social construct’ as a consequence of our increasing interconnectedness in the modern era. Christie speculated that our isolation from each other and these industrialised rhythms might be the cause of our sense of endless time under lockdown. Ronan Love, while accepting the explanation of technology’s mediation of our concept of time in Christian’s article, felt that Kosseleck’s work had more to say on our current sense of timelessness. He argued (from Kosseleck) that our sense of time is imbued with ‘expectations of the future’, and that people’s expectations of the future had disappeared under covid, thereby leaving us in a timeless state. He also noted that notions of past time also impinged on the present, ‘the traditions of the past preying on the nightmares of the living’, as evidenced by the constant referencing of WW2 during the pandemic, leaving time under covid situated in a new matrix of past, present and future. He added that although we could be considered to be living in revolutionary and therefore rapidly changing times, he speculated, from his own research, that the experiences of the French revolutionaries were less that time was racing ahead and more that it was moving very slowly. Gah-Kai Leung noted that the original meaning of revolution was indeed a return to the beginning.

Hanan Fara noted Heidegger’s comment that we realise the conception of time in relation to our own mortality, and suggested that the imminence of death had altered our perception of time. Niall Gallen picked up on this, rooting our change in perception of time in entropy and uncertainty. He argued that both the confrontation of our own mortality and the break-down of mechanised ‘clock-time’ under lockdown had caused a profound uncertainty about what would happen next, leading to a new temporality. Fara noted that in Islamic and other religious communities, the onset of covid had been initially met with a degree of fatalism, as sense of ‘if it is my time, I will go’, and that fear had only risen at conceptions of impairment rather than death. She pointed out that for those for whom death was not considered the end, time was not bounded by mere mortality. Christie noted the recounting of a sparrow’s flight across the Great Hall at Geffin in Bede, as a Christian analogy for man’s duration as life on earth, and the different sense of time this implied. A discussion of an apocalyptic end to time developed. Alastair Gardner noted the prevalence of eschatological beliefs from the Christian tradition that assumed time had a fixed end point and noted that these beliefs had ongoing secular analogies in fears of nuclear annihilation and catastrophic climate change and perhaps now from global plagues. Richard Kendall (referring to the work of Paul Kosmin) explained that such notions of the end of time had their origins in the Selucid Empire (312BCE – 63BCE), which, by adopting universal time, led rebellious subjects to create apocalyptic time frames that predicted the total end of history. Sadegh Attari suggested that our lack of understanding of the course of the pandemic had revived assumptions that the end time would come.

Gardner, contemplating historical perceptions of time more broadly, noted the conception of the current geological epoch as the anthropocene, and Braudel’s ‘deep time’ whereby the ‘events’ of today were merely ‘crests of foam that the tides of history carry on their strong backs’. He drew attention to Hartog’s view of ‘regimes of historicity’ who argues that we currently exist in a state of all-pervading ‘presentism’ where the present turns to the past and the future only to valorise the immediate. Love suggested that before the pandemic we were already experiencing a sense of ‘no time’ as everything was moving so fast that there was a sense of ‘time compression’. The creation of modern notions of time was explored by several members. Gallen noting that clock-time was invented to measure labour, Love also noting its origin in factory work and Leung the role of railway timetables in regularising time, and the 1884 International Meridian conference that established the world’s time zones. Christie speculated that the collapse of nine to five work and commuting patterns during the pandemic might have permanently altered these rhythms of time. Fara noted that these patterns were not universal, referring to the Norwegian island that had elected to abandon any notion of time, which imposed on an environment where seasonal periods of continuous light and darkness rendered clock-time nonsensical, and was perceived by the inhabitants as a kind of tyranny. Leung noted that Xinjiang had also given on time, as China’s single time zone made no sense to its inhabitants. More tellingly still, Attari and Love pointed out that the gig economy and casualisation had long since broken up the standard working day, rendering it redundant and breaking time into smaller discrete chunks. No conclusion on the permanence of changes was reached.

There was much more, join pandemic perspectives to have your say or set up your own group…